Skip to content

35 Years of the ALFSG and Animal Rights Prisoner Support

Introduction

2017 marks the thirty-fifth year of the Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALFSG). Often confused with the Animal Liberation Front itself, the SG is a separate group with its own unique and interesting history. Despite it being a small and low-profile organisation, throughout these years the SG has worked consistently to support the idea of direct action for animal liberation and to support those that find themselves paying the price of arrest and imprisonment for carrying out such acts. The history of the SG can be divided into two specific phases. The first, in its initial years of the early to mid 1980s, saw the SG act as an organisational wing of the ALF, providing theoretical and practical support to the new generation of militant activists. It did, as it proclaimed on the cover of its early newsletters, offer ‘direct support for direct action.’ After a prolonged and serious attempt by the State to undermine militant animal liberation activity in the mid to late 1980s through legal repression (including targeting the SG itself), the ALFSG reconstituted itself in the early 1990s. Since then, the SG’s remit has been to provide financial and moral support to animal rights activists who have come up against the law, in particular those that have been imprisoned in their efforts to help build a kinder, more compassionate, world. Despite episodes of repression, the SG has remained a defiant and uncompromising support base for activists who realise the necessity in using militant direct action to bring lasting change in the interests of the animals. In its effort to provide support for the animal rights movement’s prisoners, the SG has been joined in its work by a number of other sympathetic groups, namely Support Animal Rights Prisoners (SARP), Vegan Prisoners Support Group (VPSG) and Animal Rights Prisoner Support (ARPS). The collective effort of all those involved in these organisations has developed a proud tradition of support for such political prisoners and established the animal rights movement as leaders in prison support for radical activists.

The SG has always proudly stood behind the culture of militant direct action for the animals which is a central, important part of the modern animal rights movement. Through its publications and outreach work the SG has helped ensure direct action to become a mass, far-reaching and powerful activity to help animals, commanding diverse and popular support both from within the movement and outer sympathisers. Whilst the issues that surround direct action are the main focus of its work, the SG has also helped promote an ideology in the wider movement that encourages autonomous, holistic, critical and internationalist thought and action to help animals. This has helped to ensure the growth and development of the modern international animal rights movement.

Early Days

The ALF Supporters Group was officially established in 1982 and issued the first edition of its newsletter that autumn. Previously, Ronnie Lee had encouraged publicity for the ALF by acting as an ad-hoc spokesperson. As direct action became a popular activity for the burgeoning animal rights movement, both attacks and subsequent media coverage escalated. With this came an increase risk of arrest for activists and it was felt that an official body was needed to offer support for both direct action and those individuals that carried it out. An activist then put forward the idea of a supporters group to Ronnie who was “enthusiastic about it”, and with his blessing, formed the ALFSG. The consequences of two particular actions influenced this decision. The first was an unsuccessful raid on Hillgrove Cat Farm in Oxfordshire in September 1981. As the activists busied themselves in one of the catteries they disturbed the owner of the farm, Christopher Brown, who used his tractor to prevent their exit. Eleven activists were apprehended, which at the time was “[t]he largest number of people arrested for an animal rights direct action.” The arrests and subsequent trial “obtained significant publicity” and a defence campaign in support of the ‘Curbridge 11’ was launched. Unfortunately, ten of the activists were convicted, but not before running a principled defence of ‘justifiable cause’ – that whilst their action broke the law it was not a crime as vivisection was morally wrong. The second was a mass daylight raid on Life Science Research in Essex that took place on 14th February 1982 and was known as Operation Valentine. In forty minutes activists ransacked the establishment, rescuing rats, mice and dogs and causing roughly £76,000 worth of economic sabotage. Sixty people were arrested, of which twenty nine went to trial, resulting in eight receiving prison sentences. As a result “…the ALF began to realise that due to the increase in ALF activists and activity, arrests would indeed rise and appeals for cash would have to be made on a regular basis.” The SG set about to coordinate support for direct action and those arrested. Up until then support had been seen in some instances to be lacking. One who served a sentence in the late 1970’s explained; “Whilst in prison we got a few letters but it was demoralising as nothing seemed to be happening on the outside. I do feel we were let down and didn’t get the support we needed.”

Although arrests and imprisonment acted as a major influence for the formation of the SG, it must be made clear that in its initial years the SG’s main focus was not prisoner support. Instead, between 1982 and 1986 the SG acted to both encourage activists to carry out direct action and to support them in doing so through the raising of funds and other measures. Its newsletter carried many articles and letters of a philosophical or tactical nature exploring issues concerning direct action. Two common discussions were on the validity of mink liberations and property damage, both of which received criticism from some quarters of the movement. Some were concerned about the possible ecological impact of releasing a non-native carnivorous species into the countryside and others believed that whilst liberations were valid, the vandalism and destruction of private property crossed a moral boundary. Other articles explored the justness of direct action and peoples reasoning for supporting the ALF, the psychological nature of animal abuse, challenging abuser’s myths about liberated animals suffering outside the confines of their exploitation and practicalities involved in direct action. By soliciting contrary opinions in the form of letters from its supporters, the SG provided the opportunity “to give a voice to different opinions, so people could decide for themselves what they agreed with.” However, read in their totality, it appears that the initial run of SG newsletters helped to establish an unofficial policy for the ALF. This was highly important in ensuring that the ALF grew from a small, fringe group of activists to a nation wide (not to mention international) campaign of regular action. The ALF is after all an uncoordinated network of regional cells and sympathisers which act in total independence and autonomy from any centralised hierarchy. Yet at the same time, it has largely managed to establish a unique identity and consensus on what values it espouses and what tactics it utilises.

From the start the SG was keen to document the actions of militant animal liberationists. Assisted by reports in local newspapers, often supplied by Press ‘cutting’ services, supporters were encouraged to write in with news from their local area, and sometimes activists would send direct communiques. By compiling a concise chronology of activity including a date, location and brief synopsis for each action, the SG was able to establish that the ALF was not involved in mere credulous claims of ‘propaganda by the deed’ but a serious political campaign of propaganda, liberation and sabotage. Breaking reports down into regions and giving equal coverage to all acts, the two major focuses of the ALF’s campaign – liberation of enslaved non-humans and economic sabotage through property damage – both established prominence. With an increasingly regularity, the reports also announced the closure of the targeted premises after their visit from the ALF. Interestingly reports of attacks on the diary industry were sometimes accompanied by a disclaimer explaining the inherent exploitation involved in milk and cheese production. It must be remembered that at the time veganism was not considered a central tenet of the movement that it has become, but an extension of vegetarianism. Reports on liberations often contained details of the poor state of both the animals’ health and conditions they were kept in. This recognises point two of the ALF guidelines, and is at a time when video and photographic evidence was rare and complicated to produce. Through digital technology and latterly social media we have become accustomed to graphic images of animal exploitation collected from inside slaughterhouses and laboratories. None of this existed at the time and the institutional practice of animal abuse was generally secret and unknown to the public. The ALF’s campaign pre-dated the use of undercover investigations by above-ground organisations (which started in a modern form in the mid-1980s) meaning that the ALF were one of the first groups of the new generation of animal liberationists who revealed to the world the true nature of human treatment of non-humans. The chronology of ALF actions proved so popular to the movement and important in gaining publicity that the SG began to issue them separately in a dedicated publication entitled ALF Action Reports. Every month these were dispatched to “newspapers and periodicals all over the world.”

The SG also addressed the relationship of direct action to conventional politics. It recognised the limitations of “the more traditional methods of campaigning” and argued that such tactics “alone would not stop animal abuse.” Letter writing and “parliamentary manoeuvre” was all good and principled, but had been a “historic failure” in establishing the radical change of circumstances animals need. Instead, the ALF offered four points of address to instances of animal abuse; rescue the animals, make the operation of their exploitation increasingly difficult through sabotage, financially undermine it through growing repair and insurance costs and gain exposure of animal exploitation in the press through sensationalist action. The SG boasted:

More animals have been saved and public awareness of animal abuse has been effected in just 20 years of direct action by the ALF and other groups… than in 100 years of political campaigns.

In early 1984 the SG reported that the ALF had rescued 5,600 animals and caused an estimated £2,300,000 worth of damage in the previous year. However, the SG understood that the ALF could not exist in a vacuum and that other types of campaigning were “a necessary and important part of the [struggle…] each group – and each person – has its/his/her role to play.” The SG understood that the ALF was not at odds with campaigns to effect parliamentary change, but in fact made a powerful contribution to the demands. The pressure of direct action would “undoubtedly force government to legislate against animal abuse.” And if the government could withstand such a force, then the industries would start to fail as direct action would make animal abuse “a costly and highly dangerous exercise.”

The Supporters and the Supported

The SG appreciated that there were many people who were unable, for a multitude of reasons, to carry out direct action but who could still make vital contributions to the success of the ALF. These are the people who became the back bone of the subscribers to the SG and their contributions were responsible for “directly strengthening the ALF.” From the start, the SG embarked on an aggressive and often stated mission to raise funds, largely through subscriptions and donations, from its supporters. ALF activists were “usually [paying] for heavy costs… out of their own pocket” and these funds would be channelled to activists up and down the country and help cover costs incurred in carrying out raids and other actions. The money also enabled those who took care of liberated animals to feed them and pay for veterinary treatment. The number of people subscribing to the SG rapidly grew and “literally stretch[ed] the length and breadth of the country” as well as abroad. Subscribers were issued a membership card and special badge and were encouraged to get their friends to join as well. Essentially subscribers were “all those who basically supported what the ALF was up to, but who did not want to or could not afford to get personally involved in illegal actions.”

Like the movement in general, subscribers came from all walks of life, but “there was a high proportion of older and wealthier members whose inability to actually to go out on raids was due more to old age than any lack of enthusiasm.” Some of these had been concerned about animals since the 1930s and 40s yet had seen very little improvement in their treatment. They were now inspired by a new generation of radical activists who were determined to make a difference. A 1986 television documentary interviewed two such ALFSG subscribers. They were a retired middle class professional couple who lived on the suburban south coast. They explained that what happened to animals was so ‘evil’ and wrong that anyone who intervened in such abuse was worthy of support. Questioned on whether that would extend to the activists who had carried out a recent incendiary attack on meat lorries in Brighton, they responded that it ‘did not concern them as they did not eat meat!’ Merchandise was produced to capitalise on this growing support. At first subscribers could purchase photographic prints of some of the animals rescued by the ALF, before popular demand saw the SG producing its own series of t-shirts. Post and Christmas cards were to follow. Supporters also carried out their own fund-raising initiatives such as “the ladies who bravely walked through Croydon wearing only their underwear” for sponsorship money and a £26 donation collected by the South London Animal Movement at the Anarchist Bookfair. In 1985 a benefit compilation entitled Devastate to Liberate was issued featuring Crass, Annie Anxiety and a slew of anarcho and avant-garde musicians. The following year another compilation was issued, under the subtitle Artists for Animals. Featuring more mainstream artists such as the Style Council and Madness, its back cover gloriously introduced in word and picture the ALF and SG.

Alongside offering financial support, subscribers were also used to provide homes for animals rescued by the ALF. People who were able to offer homes to those animals were asked to write in with details of what species of animal and how many they could take care of. The SG went as far as to say that there would be funds available if its supporters considered establishing animal sanctuaries. Vehicles and sympathetic mechanics to assist the ALF were also appealed for by the SG. But financial support was just one way in which the SG encouraged its readers to support the ALF. One feature in the newsletter was initially called Adopt an Animal Abuser and then later renamed Enemy of the Animals. Each edition carried the personal details of an animal abuser who had recently been on the receiving end of ALF justice. Their name and address was printed alongside a description of their work and supporters were encouraged to contact them to “let [them] know what you think.” The SG understood that there were so many people involved in animal exploitation that even if someone did get targeted by the ALF, it was likely to be a one off incident. With little effort and risk to themselves, supporters could add to the pressure building on the abusers. Not only did this turn isolated incidents into the beginnings of sustained campaigns against certain representatives of exploitation institutes, but acted as the first steps towards people becoming ALF operatives. Alongside this, readers was also encouraged to be vocal in their support for the ALF, especially contacting local and national press in an effort to “counteract any possible anti-ALF letters written by animal abusers.”

It is clear that in these early days publicity was an extremely important priority and the SG was keen on giving representation to the identity of ALF activists. It has always been a habit of those outside to portray the ALF as either nihilists in an all out conflict with conventional society, or as some sort of underground army of extraordinary heroes. The SG sort to counteract these sensationalist ideas and demystify the demographics of the ALF. According to the SG all members of the ALF were by definition either vegetarian or vegan and rather then be exclusively wedded to direct action, were in fact members of the wider movement and involved with other, law-abiding organisations. It explained that:

[ALF] members come from all social classes and two members working aside each other can be of different creed, colour, political group and social background – all of which fades into insignificance when on an ALF action to rescue animals and/or destroy animal abuse equipment and property.

A lengthy interview with two anonymous ALF activists was carried in issue number two of the newsletter with attention given to their personal circumstances: they were in their mid thirties, parents of a young child, in professional occupation and residents of a moderate sized home. This profiling certainly helped challenge popular assumptions that the ALF was made up of naïve youngsters or reckless delinquents and stressed the genuine motivation of militant activists. The SG also sought to demystify the ALF within the movement. Rather than being composed of activists “endowed with near superhuman energy, intelligence and agility” ALF activists were actually “normal ordinary members of the animal rights campaign that belong and work for [a variety] of animal rights organisations…” Alongside such profiling of activists, the SG ran regular descriptive reports detailing the manner in which they carried out their actions. Coupled with articles encouraging the responsible use of arson and the effects etching fluid has on the windows of butcher shops, the SG was promoting the idea that anybody could be involved with direct action.

The Enemy Within

The rise in ALF activity did not just cause consternation amongst animal abusers and their supporters in the establishment. Its uncompromising campaign also caused tension within the movement, as the leadership of ‘respectable’ organisations that previously “provided consistent support” to the ALF sort to distance themselves from what they considered the negative publicity garnished by direct action. In May 1984, the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) terminated the use of their office facilities for the SG. Five months later, the Peace News collective in Nottingham, following an article in their paper criticising the ‘violence’ of the ALF, denied the SG the continued use of its postal box service. The SG then relocated to London, opening a contact address with the British Monomarks service and renting a small office in Hammersmith. For the SG there was a level of hypocrisy in these decisions as, for example, the BUAV was happy to use evidence gathered from laboratories during ALF raids in its propaganda and grow its membership off the back of new activists inspired by the radical approach, but could not be seen to be ‘getting their hands dirty’ by openly providing support to the SG.

In an effort to encourage the radical tendency within the movement over the more conservative tradition, the SG also encouraged its supporters to attend Annual General meetings of both the BUAV and Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and vote for sympathetic committee members and motions. Whilst appreciating that there were extremely genuine people involved with such organisations, the SG was critical of the amount of money they had at their disposal and believed the ALF could put such resources to better use. These efforts of the SG to divert support away from the moderate welfare campaigns of the RSPCA towards the campaign of militant direct action evidently had some impact on the RSPCA’s support base. In the mid-1980s the RSPCA responded by running an advertising campaign directly against the ALF. The adverts professed their ‘belief’ that helping non-humans ‘lies within the law’ and that sending them a donation would ‘achieve far more in the end than cutting wire fences.’ It was accompanied with an imagined image of an ALF activist cutting a fence with a pair of bolt-croppers.

Standing up to Repression

As the 1980s progressed direct action became more widespread and soon the ALF were joined in their campaign by similar organisations like the Eastern Animal Liberation League and the South East Animal Liberation League. The leagues mobilised hundreds of activists to commission raids in broad daylight on research facilities. The establishment struck back and direct action increasingly carried the risk of arrest and imprisonment. After a series of politicised trials of animal liberationists, the SG began to increase its focus on prisoner support. Previously, it had not given much coverage to the matter, including not even running addresses of prisoners in its newsletter. It is unclear how support for animal rights prisoners was encouraged then, but one activist involved at the time remembers “a separate sheet being included with some issues [of the newsletter] that gave prison addresses.” The SG questioned the morality of imprisoning people for attempting to help animals:

There is something seriously wrong when establishments can torture an animal to death and allow them to suffer in total agony – and be protected by the Law and those who seek (and succeed!) in prevent this obscenity are put on trial.

One problem the movement faced when arrests happened was activists cracking under the intimidation of the experience and admitting their responsibility or informing on their colleagues. Many people involved in direct action did not come from criminal backgrounds and acted out of honest intentions. They were not savvy when it came to dealing with the law and the intimidating and threatening nature of police investigations proved too much for them. The SG took a hard-line stance on such behaviour and in 1986 warned that “from now on anyone who says anything other than name, address and ‘no comment’ will not receive any support from the SG. That is how seriously we view the situation.” It is unlikely that this policy was ever enforced. Another legal issue the SG took a position on was the way animal liberationists pleaded in court. Those who fought the charges yet were convicted would get full financial support whilst those who accepted guilt would receive only 50%. For the SG it was “totally illogical to criticise the ‘system’ which pays so much into animal abuse and then wrongly plead ‘guilty’ and quickly pay a fine into that ‘system.’” Under UK court procedures when defendants come to the address the charges they face, they are not asked whether to accept responsibility but whether they accept ‘guilt.’ Guilt is a term imbued with moral connotations related to sin and obligation. It seems a contradiction for activists to do something as principled as breaking the law in furtherance of a noble cause and then admit implicit remorse. Instead, the SG contended that unapologetically going to gaol was a significant moral action in itself. Rather than deter people from action, such a stance was inspirational and argued “[e]very arrest and every prison sentence must lead to an increase in the action rather than the opposite.” People were encouraged to write to those behind bars and local networks of activists were mobilised “to help cater for the welfare of activists arrested in their area.” Demonstrations were organised outside police stations and prisons where animal liberationists were held and supporters organised rotas to ensure prisoners had a regular visitors. Sometimes these visitors managed to supply the imprisoned with food parcels. This raised the moral of the prisoners and helped them find meaning in their prison experience. One activist in gaol in the Midlands wrote at the time: “I just wanted the readers of the [newsletter] to know that I do not regret what I have done. Not for one moment do I regret it, even from the confines of prison.” A journalist who carried out an in-depth yet critical study of direct action activists observed:

It should be said, animal rights prisoners served their time with patience and considerable dignity… [l]etters from prison suggested that serious activists were prepared to accept their time behind bars as the necessary price of animal liberation.

Whilst the newsletter had started out as a “rough, cyclostyled series of sheets stapled together” by 1984 it was re-stylised as magazine awash with photographs, cartoons, press clippings and typeset headlines. In 1986 the SG clarified its activities:

The SG helps arrested activists with fines and legal expenses, assists with the welfare of those who are imprisoned, maintains several press offices in different parts of the country, gives talks about the ALF to interested parties and produces and distributes literature to educate people about animal persecution and what the ALF is doing about it.

It had previously encouraged its supporters to establish animal sanctuaries so both large numbers of animals and those saved from the horrors of modern farming could be homed. Now it issued a specific yet short-run Rescued Animal Sanctuary Fund appeal to help with the costs such places incurred. The SG also made a donation to a newly established local group, RATS, in south London. This contribution helped the group pay for their leaflet What Do You Know About the ALF? which in turn was used to fund raise for ALFSG. One final initiative the SG embarked on, but never realised, was a ‘Young’ ALF Supporters Group aimed at the under-sixteens. With a desire for young people to creatively imagine a world free from animal exploitation, it promised a special newsletter produce especially for them. However, the powers-that-be had other ideas.

Support Animal Rights Prisoners

Support Animal Rights Prisoners (SARP) was originally established in March 1985 “by people involved in the animal rights movement who felt it was vital that there was organized support for AR prisoners.” The forthcoming trials of activists involved in the mass daytime raids of the ICI, Wickham and Unilever laboratories had taught the movement that the state was determined to gaol animal liberationists and served as an inspiration for the formation of the group. SARP’s aims were to distribute “information on prisoners so that people can support them… provide funds for prisoners’ needs and for visitors’ travel costs” and encourage prison governors to accept the “demand that prisoners are given vegan food, toiletries and clothing on request.” SARP produced a monthly mail-out of prisoner addresses, a guide on writing to and visiting prisoners which included explanations on what prisoners could and could not receive (money, cassettes, food, toiletries, reading material etc.) and the odd newsletter. By 1988 it had given “over £5000 directly to prisoners and their visitors.” April 1990 saw the last mail-out from SARP as at that time it had decided to merge with the SG in order to “avoid duplication of prisoners’ support work.”

Capturing a General

In March 1986 the police raided the Hammersmith office of the SG and arrested Ronnie Lee. Having failed to halt ALF activity by prosecuting some of the activists involved, this was an attempt by the state to damage the ALF through undermining its support and publicity base. Lee was charged with a number of offences; conspiring between February 1985 and March 1986 to commit arson and criminal damage and to ‘incite persons unknown to commit criminal damage’ and was remanded to prison. The case was linked with the arrests of a London activist, Liverpool activist and a cell of nine ALF activists in Sheffield who had instigated a campaign against the fur industry; in particular pioneering a small incendiary device aimed at triggering the sprinkler systems of department stores. They became known as the ‘Sheffield 12’ and went to a highly politicised trial in January 1987 facing a cocktail of conspiracy to commit arson, criminal damage and incitement charges. Whilst there was strong evidence linking the ALF activists to actions such as the smashing of windows and planting of devices, the charges against Ronnie rested on written material published by the SG, such as The SG Newsletter, and commentary he had made as Press Officer. In the early 1990s he explained the nature of the charges:

Mainly what the charges were about is that through articles I had published in connection with the ALF Press Office and in connection with the ALF Supporters Group, the prosecution actually said I was encouraging people to cause damage to places connected to animal abuse…. nearly all the evidence against me in that case was from things I had written and from things I had published.

With the state creating a spectacle of a trial seeking to portray the ALF and its supporters as some sort of paramilitary organisation, there was little hope of a fair hearing for the defendants. In the end eleven of the activists were convicted including Ronnie, who was sentenced to three terms of imprisonment for ten years (ten years for each charge), to run concurrently. In his summary of the trial before sentencing, the senile old judge Fredrick Lawson “cited ALF Supporters Group newsletter 15 and specifically the phrase “Go out and Burn!” as the damning evidence; that because Lee supposedly wrote that phrase, then he was criminally responsible for the actions of those that had gone out and burned.”

The Pantomime’s Not Over

Following the arrests of Ronnie Lee, the SG continued to publicly represent the actions of the ALF. In this period it re-evaluated its role within the movement and went “to a great deal of trouble to stay within the law.” The newsletter was stopped and in its place appeared the Diary of Actions. Running to a handful of pages with a beautiful typeset layout, the Diary of Actions continued the work of the previous ALF Action Reports, chronicling regional patterns of direct action with the occasional photograph and explanatory text about the ALF and SG.

The SG made an effort to portray militant activists in a fresh light. This was done for two reasons: one was to counter the narrative put forward by an increasingly hostile media who were sensationalising activists as ‘animal lib. loonies.’ The other reason was an attempt to “challenge people’s ideas of the ALF”; both those involved with the movement and the wider, ‘general public.’ The SG was keen to steer away from the mysterious and intriguing image of masked activists causing damage in the night, somewhat seen as separate and different from regular animals lovers, and refocus attention on the reasons and rationale behind why people took militant action. With the advantage of its own newly purchased in-house printing press, the SG produced a series of small fact sheets detailing different areas of animal abuse and exploitation including factory farming, psychology and behavioural experiments and the Lethal Dose 50 test. It also set itself the task of responding to all received press reports of ALF attacks and assisted in the publishing of a booklet entitled Animal Liberation: The Road to Victory. The Road To Victory analysed areas of animal abuse, the history of campaigns and strategies for action.

Despite this attempt by the SG to broaden its appeal and not repeat the same programme that ended in the Sheffield trial, it appeared “that the powers-that-be [were] going to do all they [could] to force the ALFSG out of existence.” Once again, underground acts of sabotage were used by the police as a pretence to move against the organisation that proudly and publicly defended the righteousness of liberating enslaved animals and materially disrupting their oppression. Between December 1986 and April 1987 the home of the newly appointed ALF Press Officer Robin Lane was raided four times by the police. Three weeks after the April raid Welsh police returned and confiscated “1500 items including 20,000 SG fact sheets, 1500 Diary of Actions, the answering machine, shredding machine, filing cabinet and every single piece of office equipment” as well as personal items. Further raids were carried out on the homes of other SG volunteers and soon four activists, including Robin, found themselves facing charges of either “conspiracy to incite others to commit criminal damage” or “conspiring to incite others to commit criminal damage and conspiring to commit criminal damage.” The charges were a result of interviews the Robin Lane had done with regional media outlets directly following the planting of incendiary devices by the ALF in the fur departments of the Debenhams stores in Cardiff and Swansea and also at Howells of Cardiff. Failing to capture the activists responsible, the police used the action as an effort to try and finish the resilient ALFSG.

Whilst on bail for the Cardiff affair in September 1987, the police raided the home of the Robin Lane for a fifth time. This was in relation to the arrests in the previous weeks of two London based ALF activists partly responsible for a triple incendiary device blitz against Debenham’s stores in Luton, Harrow and Romford that caused a total of almost £9 million worth of economic sabotage. Working on the bizarre evidence of a police man who had apparently witnessed the Press Officer claiming responsibility for the attack, the raid was described at the time as “nothing less than a campaign of harassment and intimidation against the Press Office” and Robin was released without charge. Credible evidence has emerged in recent years suggesting that the man responsible for planting the third device was Bob Lambert, an undercover police officer who had infiltrated the animal rights movement in the mid 1980s. Now it seems that not only did the undercover police engage in serious illegal acts to further their involvement with the animal rights movement, but that these acts were used as an excuse to invade homes, harass innocent campaigners and disrupt the activities of animal liberation organisations.

In the midst of this wave of political repression, a new short-running prisoner support organisation called Victims of Conscience emerged. VOC issued a simple typed news-sheet that ran to eight editions and contained in-depth coverage of police and judicial action against activists, especially those connected to the SG and those held as a result of the Debenhams attacks. VOC main priority was to raise funds to cover “travelling expense to courts, barristers and police stations around the the UK” for activists on charges relating to direct action, rather than protest or public order offences.

In March 1988 Robin Lane and two other activists went to trial in Cardiff for incitement as a result of SG activities, one for producing literature, another for funding it and the third for printing it. A great deal of the Prosecutions case rested on the defendants being responsible for publishing and distributing a magazine entitled Interviews with ALF Activists which had detailed information on building incendiary devices and carrying out sabotage. However, “no evidence was found to show that the SG was responsible for the magazine” and with this “the prosecution’s case virtually collapsed.” The prosecution were left with the Diary of Actions and argued that “the sole intention of reporting actions was to encourage others to do the same.” Unfortunately the jury agreed and two activists were convicted of incitement. Understanding that the activists had been “’giving the ‘oxygen of publicity’ [to actions]… rather than committing criminal acts” in general the presiding judge “accepted that [the two] had only broken the law out of their belief on animal cruelty.” The activists received gaol terms of eighteen months with nine automatically suspended.

It seems that the police had intended that the operation which culminated in the conviction of activists at the Sheffield trial would be the end of the ALF. However, with actions continuing and the SG still functioning it was clear that the police had not been as thorough as they had convinced themselves they had. The subsequent targeting of the SG can been considered as an effort by the police to ‘finish the job’, as one of the Cardiff defendants later recalled:

I think the police had this idea that once they got all of the ‘leaders’ as they put it, they weren’t really expecting people to come along and step into their shoes, but we did [which] I think they were really pissed off about.

The police continued with their pattern of using the ‘conspiracy to commit criminal damage’ charge in relation to literature, as a 1988 edition of Victims of Conscience included a report of a man in Yorkshire being charged with the offence “after so-called ‘inciting literature’ was found at this home.” No further details were given on this matter. Despite these episodes of repression, “[b]y the end of the eighties… [t]he survival of the SG had been no mean feat following the successive trials and imprisonment of most of the ALF leadership…” Likewise, the ALF’s anti-fur campaign continued through the “spring and summer of 1988 and into 1989, incendiary devices continued to be planted in department stores” in Manchester, Liverpool, London, again in Cardiff, and Plymouth, with the Animal Rights Militia claiming responsibility for attacking the Dickens & Jones store in Milton Keynes in 1989.

Into the 1990’s

After a brief hiatus following the police campaign of arrests and intimation, the SG resurfaced towards the end of 1989 with a new newsletter. Minimalist in layout and often not reaching more than a handful of pages, the SG stuck cautiously to the law, publishing only short summaries of who had been arrested and for what. One edition even reported the arrest of four local journalists after they had covered the liberation of a goat in the Hendon area! In October 1991 the ALF Press Office reconstituted itself independently “to safeguard” the SG from unwarranted state interest. However, it continued to work alongside the the SG with future editions of the newsletter carrying many of the Press Office’s columns and articles.

Getting Carried Away (Again)

By 1992 the SG Newsletter had expanded its coverage of arrests and prisoners to offer detailed accounts of then on-going and recently concluded police investigations. Some were written by supporters of those victim to police attention, whilst other accounts came directly from the activists involved, often written from the wrong side of a prison wall. How they came to be arrested by the police, what premises were searched and what was taken, how they fared under interrogation and the how the charges were likely to be presented in court were common themes of articles. Often the contributions were informative, based on first hand experience, analytical and reflective. One written under the pseudonym ‘An Urban Spaceman’ recounted his interview by the police in which they had details from a letter a friend of his had sent into a prisoner. Another, entitled ‘To be or not to be paranoid?’ explained the types of intelligence police held on activists gleamed from a four week trial for a variety of conspiracy charges in Northampton. The SG also continued to offer direction and guidance to ALF policy, after a London based cell of the ALF warned Vauxhall motors that if they continued their car crash experiments on animals “then all Vauxhall cars would be considered.” Acting with a balanced view, and a sense of humour that was to become part of the editorial-ship at the time, the SG noted that some of its own workers used such cars and suggested that the ALF’s “campaign should be confined to dealers and new Vauxhall cars.”

Keith Mann was a regularly contributor to the newsletter, breaking up his remand time and subsequent fourteen year sentence with numerous contributions, sometimes more than one an issue. Rather then the standard gaol letter, Keith wrote short articles on a number of subjects, such as forensic science, media exaggerations of ALF stories and defending a need for an ALF Press Office.

With a new staff of volunteers but a memory of the events of the mid to late 1980s, the reconstituted SG had a different reason of purpose than its 1980’s forerunner. Whilst it was still firmly in favour of direct action, it could no longer provide open support to illegal acts and instead refocussed its activities on providing financial and moral support for those who found themselves in trouble with the law. The SG had expanded it eligibility criteria of financial support from those convicted of ALF actions to “all persons imprisoned in the cause of animal liberation, whether it be an ALF action, hunt sab or demo.” Each prisoner, “regardless of their so-called crime” received a monthly stipend of £25 and further funds were available to pay for newspapers, magazines, educational materials and personal stereos. After the prisoners were looked after, the SG’s remaining finances were spent on assisting their visitors with travel costs and helping to pay fines for non-custodial sentences. With regret, because of limited funds, the SG was only able to “pay out a proportion of the fines if the action is considered to be an ALF action” and this would be “normally between 25% to 50% depending on the amount we have in our building society.” The SG also encouraged defendants and their supporters to set up defence funds and allowed the use of its postal box as an address for such campaigns.

By defiantly returning to support militant activists, the SG continued to receive the unwanted attention of the authorities. Failing to stop the SG through the arrest and imprisonment of its volunteers, and no doubt aware that the activists where sticking cautiously to incitement laws, the police tried a new strategy to undermine the running of the organisation by putting pressure on the financial services it used. Deciding that the SG had compromised its “new ethical code” the Co-Operative Bank “immediately” froze its account “without any prior warning or request to transfer the account elsewhere, despite the SG having been a good customer of the Co-Operative Bank for 10 years without there having been any problems.” As a result the SG was deprived of some of its supporters’ standing orders meaning it “lost about 25% of [its] regular income in one swoop.” The SG then opened accounts with the Ecological Building society as well as two others in an effort to “limit [the] risk further.” However, by 1993 the SG was reporting that the Ecological Building society had been receiving complaints about the SG’s use of their service. With a month’s notice, the account was closed and once again the SG had to find another banking service. This second round of economic disruption followed a report on the SG by the Sunday Times and led the SG to understand the difficulties as part of an orchestrated attempt by the state: “The Supporters Group has always risen out of the ashes of any arrests and imprisonments, so perhaps this is seen as a better way of destroying us?”

Despite the 1980s prosecutions aimed at stopping the ALFSG and this new campaign of disrupting its finances, the SG remained a defiant public face of support for militant direct action. While regular efforts were taken to avoid breaking incitement laws, it was still felt that running the SG ran the risk of unwarranted police attention. With a renewed ALF offensive against the meat industry and a new generation of defiant animal liberation prisoners, there was a sense that political repression against activists was an inevitable result of the struggle. Understanding that whilst they did not wish to take unnecessary risks and offer easy arrests to the police, it was accepted that risks and potential sacrifices were required to continue the vital work of supporting direct action. Arrest and imprisonment was seen, by those involved, not as a traumatic experience that required years of reflection and soul-searching, but an occupational hazard and the natural consequence of the movement making progress.

By 1993 the newsletter was back as a fully-fledged magazine, containing commentary from the ALF Press Office and reader contributed articles, alongside its coverage of arrests, court cases and prisoners. As the page count grew, the newsletter noted that the size of each edition was determined by contributions received. In my personal opinion, this run of newsletters saw the SG reach a high point in terms of quality and contribution to the movement, with informed commentary and recurring contributions from regular authors, alongside philosophical and tactical letters and exchanges, with discussions of certain issues playing out over a number of issues of the newsletter, offering a real forum for developing the movement. One such topic of recurring debate was the use of violence and the relevance of pacifism to the ethos of the animal rights movement. Whilst the SG did not offer comment further than its already established position that it did “not recognize” actions that were contrary to “the ALF policy of non-harm to (or undue endangerment of) life” it did allow its pages to be used for a number of contributions discussing the merits and cons of such positions. The two general causes that prompted the discussions was on-going state and hunt violence (i.e. protesters being on the receiving end of violence) and the appropriate response, and a resurgence of actions by the self-styled Animal Rights Militia, including a claim that they had contaminated a number of Boots products with glass slivers and paint stripper throughout southern England. The latter received condemnation from both the ALF Press Office as well as Ronnie Lee.

Another issue that drew strong response was the relationship of fascism and the far-right to the animal rights movement. It was first raised in a hard-hitting letter written by two serving prisoners entitled ‘Fascism & Animal Liberation: Expose them and beat them, but never ever condone them.’ Against a background of rising far-right political parties in Europe and the attempted infiltration of the movement by fascist groups like the Patriotic Vegetarian and Vegan Society and the National Front’s ecological spin-off Green Wave, the authors made their positions perfectly clear:

What has this got to do with animal rights, you may ask. Well, think about the the nature of fascism, the senseless hatred of racism. A world free of animal abuse is inconceivable unless we are prepared to simultaneously rid ourselves of all oppression. Fascism is humanity at it’s most abusive, most oppressive – and until such horrors are eliminated liberation will always merely be a light at the end of the tunnel… We can talk about vivisection as being the ‘Animal Belsen’ but what about the sheer realities of it all, the persecution of those whose cultures differ, the repression of us all, given the chance. Fascism breeds only ignorance and hate.

The authors concluded the letter by celebrating the mass Anti-Fascist Action mobilisation that had disrupted the organisation of a neo-nazi rock concert at Waterloo station earlier in the year, describing the event as “a good example of how to deal with these scum” and that “there must be a ‘Waterloo’ every time they rear their ugly heads.” The SG followed up with its own statement that outlined a strong, measured and thoughtful position. Recognising the political diversity that exists within the movement and seeking to avoid alignment to any particular political ideology, the SG roundly denounced “all racist and fascist groups without reservation.” Its logic was simple and straight forward – the movement fights for equality for all animals, including humans, and any ideology that seeks to undermined that and accentuate the arbitary differences between people because of “their [skin] colour, creed, religion or place of birth” is in contradiction with this, meaning “fascism is incompatible with the philosophy of animal liberation.” It is important to remember that there is a strong principle of internationalism that runs through the movement. Non-humans recognise no nationality nor geo-political border and as a result when it comes to helping animals advocate should neither. When it comes to protecting animals, there is little difference between disrupting fox hunts in England to helping street animals in Asia or releasing captive mink in Russia for example.

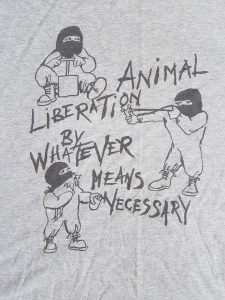

Along with this expanded content, a new lay-out style was used, made possible by the emerging prevalence of new desk-top publishing technology such as DTP software. The software allowed the easy creation of computer processed text. Empty page space was then, “for aesthetic reasons”, filled with inspirational quotes from an eclectic mix of famous thinkers and artists such as John Paul Satre, Malcolm X, Manic Street Preachers, The Pogues, Peter Kropotkin and even Yoda was used to tell readers “Do or do not, there is no try.” Alongside the quotes the first attempt at some original humorous cartoons appeared: The caption ‘Sssh! Walls have ears!’ accompanied a drawing of a mask figure climbing the fence into a sausage factory. Soon, the SG had its own mascots, with the Winter 1992 – 1993 edition first featuring the iconic cartoons of a balaclava’d figure called Alfie, often accompanied by his animal friends. Soon Alfie was joined by a side-kick called JD, a giant rat who often waved a massive stick and encouraged a more aggressive line of reasoning than his cohort. The editor at the time explained: “[t]he subtext of characters was that JD was putting the animal’s side of things and as such was more more radical and willing to go to greater extremes.” The Alfie and JD cartoons cheekily depicted a number of scenarios; being chased by the police, liberating bottles of alcohol, relaxing after a busy night out with a catapult. One t-shirt design which showed Alfie with a detonator and the words ‘by any means necessary’ was pulled on legal advice after the barrister “freaked out” upon seeing it. Another regular feature of the time was the page entitled ‘Prisoner of War’ which sort to list every person who had ever been imprisoned as a result of animal rights activity since 1975. It was an effort to celebrate the wide-reaching commitment of those that defend animals. When it was last run in the Summer 1995 edition, the number of serving and former prisoners, including recidivists and those from Canada, France and the USA, stood at 181. Desk-top publishing was not the only new technology the SG embraced, in 1994 it first established an email account – now long defunct 100302.1616@compuserve.com.

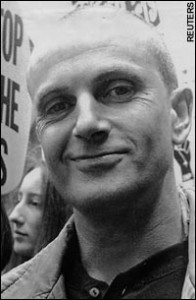

At this time the SG maintained an ‘action list’ of reliable supporters who would be alerted in the first instance when a new activist was imprisoned. This was to insure that such activists were provided with moral support in their initial days of incarceration. The SG also promoted this alongside the idea of ‘pen friends’ for non-political vegetarian and vegan prisoners. It also issued to new leaflets. One, entitled This Young Man Helped Rescue Beagles from a Torture Lab… His Reward was Prison was a general introduction to the work of the SG and prisoner support. The other, issued in conjunction with the Animal Liberation Investigation Unit exposed pesticide and other chemical tests on animals conducted by the company Rentokil. It was produced following a raid of their premises in Felcourt, Surrey in which the ALF liberated forty mice. For the Winter of 1993 the SG produced four fund-raising Christmas cards featuring its new mascot Alfie.

The Second Fitna

These years also saw inter-movement tension surface again. One the one side was the ALF and ALFSG and on the other, ‘the nationals’, notably the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS), Lynx and Animal Aid. The nationals point of view was, that by breaking the law, the ALF brought the animal rights movement into disrepute. Furthermore, its militant actions were actually counter-productive to the struggle for animal liberation as the heavy press coverage focussed on law-breaking rather than the animals. The militant point of view was that not only did the ALF take the fight directly to the animal abusers and save lives, but that it was popular: it had mass support and the publicity created by its actions raised the profile of animal rights, drawing new people into the movement. The discord originated from press coverage of ALF actions, in which rather than use the opportunity of publicity to focus on animal exploitation, certain spokespersons of the nationals preferred to condemn militant attacks in an effort to present animal rights people as moderate and civil when it came to issues of depredation, torture and murder. The trouble escalated in June 1993 when the SG and Press Office were refused a stall at the Living without Cruelty festival in London. With a feeling that “the plight of the prisoners and of the existence of the ALF in general should be publicised” the SG “resolved to still attend” and established their stall “outside the event so the first thing punters saw was the ALFSG staff… many [attendees] were outraged we were not allowed inside.” In an effort to stop the SG, the organisers first called the police, and then as it was a civil issue, the local council who responded with disinterest. Rather than diminish the profile of the ALF, the drama, with the SG stall being literally ‘front of house,’ ensured sympathy and support for both the SG and direct action in general. Reporting on the event, the SG at the time sort to play down the disagreement, suggesting it was more the work of one or two individuals at the organisation, rather then the organisation itself. It stated “[w]e do not want to squabble between ourselves, the animal abusers are the enemy. All else becomes unimportant next to that fact.” Similar tensions occurred at that years and the following years World Day for Animals in Laboratories rally, where NAVS banned the distribution of pro-ALF literature. Following the demonstration in London, NAVS had convened a exhibition – yet grass roots activists had established an alternative exhibition with “stalls and events” for “those groups not in favour with NAVS (for whatever reasons), or just too small or poor to be able to afford the £350 stall fee” attached to having a place at the NAVS’ World Day exhibition. The SG urged “all to come to the World Day demo, visit both events on offer and from that perspective decide who does the most for the animals with their resources, and support them accordingly.” Thankfully, in recent years the the relationship between the SG and Animal Aid is much more cordial. And peculiarly with the collapse of grass roots and militant anti-vivisection campaigns, NAVS have failed to capitalise on the relative peace and offer their own successful campaign to fill the vacuum. Conversely they have seemingly disappeared, proving perfectly the fallacy of their logic – direct action is not the movement’s weakness, but indeed its strength. When we are diverse in tactics but unified in effort as a movement we are strong. When we turn our backs on each and suggest that only ourselves realise the correct path to animal liberation we end up isolated, alone and unable to function.

Restricting the Oxygen

By offering the pages of its newsletter as a forum for opinion, comment and debate from its supporters the SG put itself in sticky position. On the one hand it aimed to give a voice to those that supported law-breaking in furtherance of animal liberation, whilst simultaneously it had to make careful effort to not fall foul of incitement laws again. It felt that is was important “not to ignore events” such as the emergence of the violent Justice Department, who ran a sustained campaign of minor letter bombs against animal abusers, as “such events… bring fundamental change to the way we perceive the movement” but that “[d]ue to legal restrictions we are limited by what we can print and feel that by allowing an open forum to the movement, we not only aid it, but make a more interesting newsletter.” Once again, the services of a barrister was used to proof-read each edition of the newsletter and flag any content that could be seen as breaking incitement laws. The SG considered the implementation of incitement laws as arbitrary, explaining that they are used reactively within a context of mass activity, rather than applied across the board to any material of a certain type. Referring to other non-animal rights publications that gave “detailed instructions on making incendiary devices” and an anarchist group that urged “its readers to violent revolt against the state, in general and particularly against the police” the SG noted that neither received the type of attention from the police that the SG had. It came to the conclusion that because the animal rights movement was actively prepared to regularly take the law into its own hands, incitement charges were used against the movement not because of the nature of the content per-se, but because it addressed the animal liberation movement:

The truth of the matter lies not with the actual events urged or what they are inciting others to do but on the past record of events. ‘Class War’ can urge its readership to burn down police stations and the Houses of Commons to their hearts content, but the establishment knows that this is an event unlikely to occur even on a small scale. Whereas if we urge our readers to raid a laboratory or smash animal abusers windows then these events are very likely to happen. It does happen without our urging time and time again, and because it does we cannot print the truth about it because it would incite or encourage more similar actions.

The efforts of the police to restrict the content of the newsletters was seen as a testament to the effectiveness of the ALF. As a result of such a situation the SG had to be careful with its content. The ‘Diary of Actions’ was no longer featured as it had been used as prosecution evidence in the trials of the 1980s and other contributions to the newsletter were edited and had parts removed. Of course, you cannot please all the people all the time, and some supporters accused the SG of censorship!

Despite this careful effort, in the summer of 1995 the SG was raided once again by the police, which stopped the publication the winter edition of the newsletter. Although no charges arose from the raids at the time, the SG became even more cautious of the content it published and declared that it had become “impossible to have free discussions on any issue… without it being blatantly inciting” and appealed for contributions that were purely factual in content. As activists started to write about either long past actions or things that were a matter public record due to court cases, even these could be provocative in content. One such hilarious example was a letter from a prisoner serving time for their incendiary blitz against Ensor’s slaughterhouse in Gloucestershire. Reporting on the details of their recently concluded court case, the author forensically detailed the events that resulted in their imprisonment:

…we dropped off our tools, petrol and the devices at the compound and drove off to park the van somewhere inconspicuous…. [a] hole was cut in the fence at the opposite end of the compound to where the police or security would so as to ensure we wouldn’t have our escape blocked. We then smashed each vehicles side window relatively nice and quietly with a centrepunch.

As they describe at length how they went about starting the fires, they began to explain the construction of the incendiary devices, and at this point editorial comment kicked in explaining that this section been restricted “because the ‘thought police’ might get on our case if we went into any further detail.”

Crossing the Line

In 1995 the SG, for the first time in its existence, after serious consideration made the decision not to financially support two animal liberation prisoners. As part of the campaign against live exports in the south east, the White Hart pub in Henfield, Sussex was subject to an arson attack and eventually two activists found themselves behind bars. The reason for the action was that the two Revell brothers who ran International Traders Ferries, used to export live calves to the continent, frequented the establishment. With such a tenuous link to animal exploitation, coupled with the fact that family who ran the pub were on the premises at the time and had to escape the fire, it was decided that this was neither an ALF action nor a just act in itself. However, despite offering no financial support to these prisoners, the SG gave coverage to the case and included their prison address, so that people “could make up their own minds” on whether these prisoners were worthy of support.

GAndALF

The raid on the home of SG editorial staff in 1995 was the beginning of a long-running and complicated incitement prosecution of radical animal rights and environmental publishers, culminating in a deeply controversial and far-reaching conspiracy trial. It was another attempt by the police to “shut down the SG and Press Office.” On the 16th January 1996 the police returned to the home of the SG editorial staff as well as raiding properties belonging to the Press Officer and four people involved with the ecological action magazine Green Anarchist. The editor at the time recalled that although the police “took the computer and all paperwork” there was also:

…a file which had all the articles showing before publication and after publication which showed how the barrister’s advice was followed. There was also a folder of receipts. The police attempted to leave these behind but I insisted they take them as evidence.

Soon six activists from the SG, Press Office and Green Anarchist found themselves charged with ‘conspiracy to incite persons unknown to commit criminal damage.’ The charges against the Press Officer were adjourned before trial. The activists quickly became known as the GAndALF defendants. A circular from the time explained the nature of the prosecution:

Six defendants are charged with unlawfully inciting persons unknown to commit criminal damage. Not only are the persons unknown, the dates when the unknown offences took place (over a five-year period!) are equally unknown, the alleged damage is unknown and even some of the defendants were unknown to the others until their arrest in January 1996.

Essentially the police had rounded up two animal liberationists that gave publicity to the ALF, as well as four unrelated environmentalists who had published news on direct action and accused them of working together to encourage people to break the law. According to one of the defendants, after spending eighteen hours in police custody, “the police were bemused that [they] had to introduce themselves” to the other defendants upon release as they did not know each other. A defence campaign was established which raised funds for the defendants and organised demonstrations and public meetings.

The trial started on the 27th August 1997 and was presided over by Judge David Salwood, who was a keen sea-fisher and later a convicted paedophile. Following legal arguments one of the defendants had his charges adjourned and was scheduled to face court alongside the Press Officer in a second trial. The first trial ran for twelve weeks in total and a had a simple premise – that the ALFSG newsletter alongside a slew of radical ecological and anarchist publications were inciting as they reported on direct action. It was clear that the police had over-stepped themselves in their investigation as giving evidence in court they made clear that they considered “any mention of ALF actions was inciting.” In defence The SG Magazine’s editor argued that he was “aware of incitement laws and their complications” and not wishing to breach them he had consulted a barrister prior to publication. The barrister would proof-read any editions of the magazine and advise on the removal of content that could be considered inciting, which the editor duly followed. Evidence was then produced by the defence that demonstrated this relationship and the editing of potentially inciting material. In cross-examination the editor was asked if they did in fact support the ALF which lead the judge to express surprise when they replied that they did and “would have to be a split personality to run the SG and not support the ALF.” By being able to demonstrate that they had “made clear provable steps” to not break incitement laws, the editor of The SG Magazine was found not guilty. Unfortunately, their three co-defendants were not so lucky and after being found guilty received terms of imprisonment for three years. After four and half months in prison, the three were released pending an appeal of their conviction. The appeal was successful and as a result the planned second trial of the remaining two defendants collapsed.

The mixed verdict of the GAndALF trial had massive implications for counter-cultural publishing, human rights, freedom of thought and freedom of speech. Much has been previously written about this and here is not the appropriate place to explore the events in further details. However, it remains to be stressed again that the nature of the ‘offences’ was farcical: a load of people from across the country, who did not know each other, finding themselves facing gaol time for inciting no-one in particular to break the law, by reporting the fact that in our society some people go out there and do things like breaking windows.

Vegan Prisoners Supporters Group

In 1994 a recently released prisoner wrote to the SG with their concerns about receiving a vegan diet in prison. They commented “[a]nybody who has been to prison will know that the standard of food is generally poor. The little that is spent on catering is now under attack of the Government’s desire to make cutbacks in public spending.” That wanted people to write and complain to the Home Office. Simultaneously, a new initiative to help prisoners receive a satisfactory vegan diet was being launched, called the Vegan Prisoners Supporters Group. It was to become one of the most unrecognised yet successful examples of vegan outreach that this country has ever seen. Initially, the VPSG was founded to assist the support campaigns for two serving prisoners, Keith Mann and Angie Hamp, with “no intention to stay in existence after they had both been released.” But after another Animal Rights prisoner contacted the VPSG on Christmas Day to complain about their meal of “cold corn on the cob”, it became clear that they had much work to busy themselves with. Soon “it was decided that [the] VPSG should broaden out to cover all vegan animal rights prisoners of conscience.” The SG worked together with the VPSG and regularly carried reports and updates from it in its newsletter. Now a new twinned prong approach to animal rights prisoner support was in action, with the SG providing financial and moral to support to prisoners and the VPSG insuring such prisoners were able to properly practice their vegan beliefs. A comic was issued entitled Do you believe in the ALF? telling the story of some cats and rodents held prisoners in a laboratory who are liberated by activists, one of whom subsequently gets arrested by the police and imprisoned. It was sold in order to raise funds for both organisations.

Run by a small number of extremely dedicated volunteers, the VPSG made it its duty to contact prisons and police stations around the country where animal rights activists were being held and assist the authorities in providing adequate vegan meals to them. A ’24 hour Emergency Arrest Helpline’ was set up so that people could inform the VPSG of any new vegan detainees. In its newsletter, the VPSG explained its procedure:

…upon hearing an [animal rights prisoner] has been remanded or sentenced… we immediately telephone the court to establish where [they] are being sent. Then the governor of the relevant prison is contacted to inform the prison they have a strict ethical vegan on the way. We also offer our free reception pack of vegan toiletries and information on nutritional requirements of vegans.

With supporters on the outside directly communicating with those in the higher echelons of the prison hierarchy, it became less easy for prison staff to ignore the demands of individual vegan prisoners. Two prisoners at the time expressed their gratitude to the VPSG explaining “[a]fter two days of dry toast and grilled tomatoes or boiled potatoes and cabbage, our vegan meals began to improve.” The VPSG also issued a regular newsletter which contained coverage of their work alongside letters from the prisoners. The content of such letters was different from those published in the SG, as they tended to focus the prisoner’s experiences of being a vegan in prison and the difficulties they faced.

The first major course of action for the VPSG was to lobby “the Home Office into reviewing its whole approach as to how the issue of veganism” was treated by the Prison Service. Whilst prisoners were previously able to receive vegan food in prison, the quality and availability varied from prison to prison, and many were deprived of satisfactory food and toiletries. For example, around this time, Keith Mann had difficulties in obtaining vegan toiletries whilst Barry Horne, held in another prison, was “without a suitable vegan margarine.” In 1996 the VPSG’s hard work paid off and they were given “the opportunity to give their input into Home Office documentation with regard to the care of vegans behind prison walls.” Their efforts were successful, and shortly after the Home Office issued new statutory regulations on the care of vegans with in the prison system. It is a remarkable, comprehensive and wide-reaching definition of ethical veganism, which opens

[v]eganism is not a religion but a philosophy whereby the use of an animal for food, clothing, or any other purpose is regarded as wholly unacceptable. The majority of vegans are non-speciest and reject entirely anything which has its origins in exploitation, suffering or death of any creature.

The guidelines covered not only what vegans can and cannot eat and wear, but what toiletries they require and “aspects of social functioning” such as the avoidance of “any sport, hobby or trade that directly or indirectly causes stress, distress, suffering or death to any creature.” Whilst the Home Office was facilitating the arrest and imprisonment of animal liberationists it was simultaneously recognising the validity of their beliefs.

However, even though policy was established, it remained the VPSG’s work to ensure that it was put into practice in prisons across the country. Each gaol is run under the discretion of their individual governors and catering products are supplied by different companies in different regions. This means there is discrepancy between the treatment a vegan prisoner would receive in the south west than the north, for example. In the VPSG’s experience “some prisons [were] more co-operative than others.” A Catering Information Pack was produced that explained the Home Office guidelines on vegans and went into great detail on how to provide a varied and nutritional diet to vegan prisoners. Accompanied with its own VPSG cookbook, the pack was dispatched to the catering department of “all 135 prisons” within the UK. It reported such an action had “altered considerably” for the better the attitudes of prison staff in dealing with vegan issues.

The next major mile stone was for the VPSG was to ensure that all vegan prisoners received, free of charge, ethical toiletries. Previously, they had been providing out of their own funds a “reception pack of toiletries” for animal rights prisoners. Again they were successful with this campaign and it had a far-reaching conclusion. Rather than issue specialist toiletries to the small number of vegans within its ‘care’, the prison service changed all the toiletries they issued, including toothpaste, to vegan-suitable products. This meant that all people serving time in prisons up and down the country were issued with cruelty free toiletries, whether they were vegan or not! By 2000 the VPSG was reporting that it had “dealt with well over 60 prisons (some several times) and 32 different government departments” in the past six years. It had also offered its now expert experience to animal prisoners in both Sweden and the USA. With such a record of achievement, the VPSG compounded its efforts and issued a report of its work to the Home Office. The report conferred “the lack of care of vegans in prison” and demonstrated “that without the help of a group like the VPSG, life would be a lot more difficult for vegan animal rights prisoners detained within the prison system.”

February 2002 saw the launch of the VPSG website. The website provided the addresses of animal rights prisoners as well as basic information aimed at vegans facing imprisonment. This was followed by a second website aimed at providing appropriate information to prison staff on how to care for vegans. Having dealt with the needs and concerns of 195 individual prisoners by 2002, the VPSG had established itself as the authority on veganism within prison and was adept at dealing with the challenges they faced. Case workers were then dedicated to individual animal rights prisoners who were having particular problems, such as finding meat in their food. They would hold meetings with both their prisoner and the relative prison staff, such as those in charge of catering, and assist in finding solutions. One such problem that arose was the lack of vegan products available for prisoners to purchase in the prison canteen. This was first raised in a meeting held between the VPSG and representatives of HM Prison Service in early 2003.

The campaign to make specialist vegan products available through the prison canteen was a long running one. Those in prison are allowed each week to spend a small amount of money on a limited selection of personal items such as tobacco, toiletries, confectionery and junk food. Whilst there is a variety of products available, very few are suitable for vegans: “Research showed there were over 114 protein items, 118 confectionery/biscuit items and 120 body care/beauty products, but not one of them suitable for vegans.” The VPSG considered this a case of discrimination, and whilst working to address this issue with the prison service, encouraged those in the movement to contact their respective Member of Parliament on the matter. While they were trying to change this situation, the VPSG used a stroke of ingenuity to ensure the movement prisoner’s received a little something extra to supplement their diet. Claiming they were doing research on new products, and just coincidently choosing test subjects who were all animal rights prisoners, the VPSG contacted the prisons where each were held, and managed to convince the staff to allow each prisoner to receive a box containing nuts, seeds, braised tofu, chocolate and multivitamins each month. This project ran for a number of years before one particular alert junior member of prison staff checked the post one morning, and seeing a box of food, alerted his superiors. Despite boxes of supplies going to a number of prisoners each month for the past few years, it was actually against national policy for prisons to receive food products from the outside world! After years of bureaucratic struggle, the VPSG managed to eventually come to a compromise where vegan prisoners were entitled to order products off a specified list from a designated whole-foods company.

With a successful, though at times challenging, relationship with prison authorities, the VPSG was able to establish itself as well respected, though unofficial, advisory body to the prison system. In order to further this relationship, in the interests of being most effective for vegan prisoners, the VPSG began to professionalise its imagine. Whilst still working directly with animal rights prisoners, it dropped its public coverage of them in the belief that if the authorities saw the VPSG as a vegan advice agency rather than political prisoner support group, they would be more receptive to their ideas. Alongside the newsletter produced for the movement, the VPSG began produce a second version aimed at prison governors, catering managers and those in charge of prison shops. In early 2005 another mail out was done to every prison in the country containing nutritional wall charts, “cookery books and additional nutritional information.” This was followed in 2011 by a special Yuletide Vegan Recipe booklet and another one giving suggestions for sandwich fillings.

Run on a small budget from the front room of one of its members, the VPSG had an incredible impact in improving the treatment of vegans within prison. Through immense commitment, extraordinary dedication and a good dollop of charm and sweet talking, the VPSG was not only able to improve the lives of individual animal rights prisoners, but establish in policy legal requirements recognising the rights of ethical vegans within prison. But its work had further impact, as prisoners who worked in prison kitchens became educated about veganism. Now, we are in a situation where ‘criminals’ in prison are able to receive better quality food then those under the care of other ‘public services’ such as hospitals and schools, and this is all because a small number of people were prepared to act when they saw those going without.

The Calm and The Coming Storm